According to Hick, there are two main types of theodicy in Christian theology: the Augustinian type and the Irenaean type. Over the centuries, the Augustinian type has dominated the theological setting. For Hick, in the past its central foundations have been taken for granted, today they lack scientific, moral, and philosophical authority, the FWD seems “radically implausible.”[4] For these reasons, Hick calls for a repudiation of the Augustinian type of theodicy as suffering from “profound incoherence and contradictions,” standing aside for the Irenaean type to emerge as the long-lost alternative to save the day.[5]

There are three major objections to the Augustinian theodicy that Hick lists. First, it was founded on an ancient cosmology and mythology at odds with modern science, which diminishes its intellectual credibility in the contemporary world. The mythical narrative of Adam and Eve has been replaced by the scientific account of evolution, which does not trace evil back to a singular event or a primordial couple, but to the ongoing struggle of life, forcing Christians to re-examine tradition doctrines of creation and original sin.[6]

Second, Hick appeals against the morality of the FWD. When we agree to take the Augustinian historicity, we are forced to accept that the blunder of Adam and Eve results in the corruption of creation and, consequently, the guilt and punishment of subsequent generations. Considering the dignity of an omnibenevolent God, Hick insists that we can no longer accept a worldview where God punishes all of humanity for all time and eternity for a minor youthful infraction by any present-day standard.[7]

Third, Hick asks how evil could appear in a perfect paradise.[8] Hick rejects the notion that evil could arise in a perfect paradise as self-contradictory: “It is impossible to conceive of wholly good beings in a wholly good world becoming sinful. To say that they do is to postulate the self-creation of evil ex nihilo!”[9]

Building the Soul-Making Theodicy

To start, SMT overturns the FWD account to make it more compatible to contemporary scientific, philosophical, and theological sensibilities. At the beginning, instead of being as fully formed, spiritually and morally mature adults, we begin as children, Irenaeus speaks of Adam and Eve as children in the process of maturation, and Hick uses that picture to construct a rival theological anthropology that agrees with evolutionary science.[10]

Hick repaints traditional theological anthropology based on his evolutionary-Irenaean framework. Hick redefines Gen. 1:26 to accord with an evolutionary scientific model of the gradual intellectual, social, and religious development of homo sapiens and an Irenaean theological model of the gradual intellectual, ethical, and spiritual development of humanity. Creation, he suggests, discloses in two stages: creation in the “image” of God and creation in the “likeness” of God. God creates humanity with the innate potentiality for “knowledge of and relationship” with God, which constitutes the first stage of God’s creative work.[11] The second stage of creation involves the realization of divine likeness through the proper exercise of their freedom. Humanity, then, slowly actualizes their capacity for spiritual contentment. While Hick presents his two stage theory of creation at the macro level, it similarly applies to the micro level. We change, collectively and individually, from spiritual imperfection to spiritual perfection.

According to Hick, perfection lies in the future, not the past.[12] We never lost paradise and we cannot return to a fictitious Garden for finding our identity. We must look forward, not backward, for insight into our spiritual nature and destiny: “We cannot speak of a radically better state that was; we must speak instead in hope of a radically better state which will be.”[13] God does not create us in “a finished state.”[14] Instead, we are “still in process of creation.”[15] We begin at an “epistemic distance” from God, a distance we must navigate throughout our lives and, as we will see, beyond our terrestrial existence, to achieve divine likeness.[16] Put simply, we are works in progress, collectively and individually. Like children, we make mistakes and, if we are wise, learn from them. As we try to find our spiritual and moral footing, we inevitably make several missteps. When we fall, as we all do, God does not punish us like a cosmic judge for the sake of God’s slighted justice. Instead, like a parent, God picks us up, dusts us off, and has us continue on the journey toward divine likeness.

Unlike the grim Augustinian portrayal of “the Fall,” SMT totally re-forms “the fall,” with a lower-case “f,” in existential terms: “The reality is not a perfect creation that has gone tragically wrong, but a still continuing creative process whose completion lies in the eschaton.”[17] The fall signifies the “immense gap” between our present spiritual state and our future spiritual destiny.

Evil, then, erupts into creation not through the sin of the primordial couple but through our missteps and mistakes as we steer the gap from biological life (Bios) to spiritual life (Zoe).[18] Hick describes sin as self-centeredness, the natural state of biological life, and the spiritual life as other centeredness, which Christ exemplifies.[19] In order to achieve our potential for divine likeness, we must progress beyond our biological instinct for self-preservation and self-advancement to attend to the good of the other, even at one’s own expense.

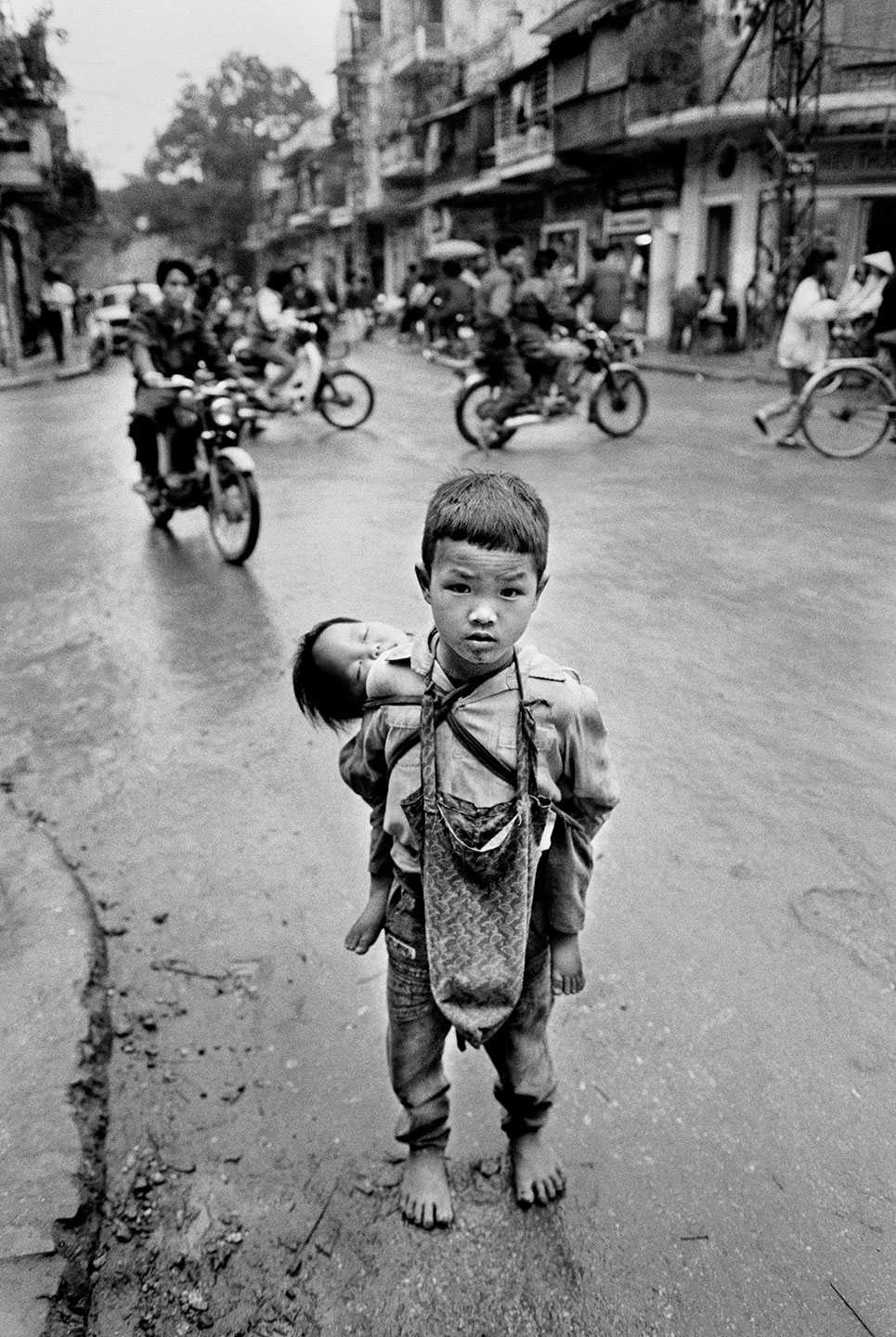

The problem of evil, however, still remains: Why did God not create us fully formed, without the capacity to sin, and thereby bypass the soul-making process? These questions bring us into the centre of the SMT view of the purpose of creation and the soul-making design of the universe. God does not create the world for our pleasure, to satisfy our self-indulgent longings. Contrary to Hume, who thinks the best of all possible worlds would resemble a hedonistic paradise, Hick thinks the best of all possible worlds is more closely similar to a classroom. The purpose or goal of creation is to facilitate our intellectual, moral, and spiritual development, not to maximize our comfort and minimize our pain. Without obstacles and challenges, we would slide into spiritual stagnation, atrophy, and apathy. To emphasise his point about the pedagogical function of the world, Hick invites us to imagine a world without suffering. In a cosmic crib, however, we could not develop compassion, courage, and sacrifice: “It would be a world without need for the virtues of self-sacrifice, care for others, devotion to the public good, courage, perseverance, skill, or honesty.” The learning of these core human virtues depends on more precarious cosmic conditions: Such a world requires an environment that offers challenges to be met, problems to be solved, and dangers to be faced, and which accordingly involves real possibilities of hardship, disaster, failure, defeat, and misery as well as of delight and happiness, success, triumph, and achievement. God, then, treats us not as pets, whom we spoil, but as children, whom we cultivate, sometimes with painful lessons.

Soul-Making Theodicy and the ‘Evidential’ Problem of Evil

Although atheists might appeal to evil in general as evidence against God’s existence, they typical take a different approach which point to either the sheer amount or the apparent gratuitousness of evil.

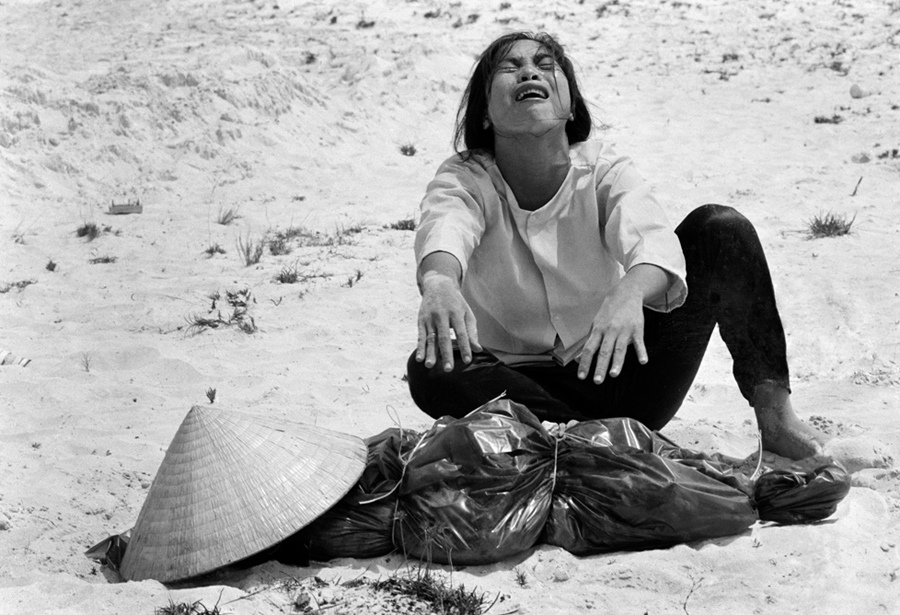

Hick, however, does not perceive the world through Pollyanna lenses, where all suffering carries about some evident goodness. He acknowledges that not all suffering contributes to our progress. Some suffering simply destroys, without any redemptive or constructive value: “But too often we see the opposite of this [good coming from evil] in wickedness multiplying and in the disintegration of personalities under the impact of suffering: we see good turned to evil, kindness to bitterness, hope to despair.”[20]

Hick rejects any direct or simple correlation between suffering and spiritual growth. As we see from even a quick glance at history and the world around us, suffering destroys at least as often as it builds. So, Hick’s SMT does not lose sight of the grim reality of suffering as it develops the theory of the constructive potential of pain for human growth. Hick refers to the “surplus” of evil, that is, excessive, pointless, and destructive suffering, as “dysteleological evil.” [21]

Nevertheless, indiscriminate, disproportional suffering—what Hick calls the “mystery of evil”—still contributes to the soul-making design of the universe at a macro level, since it cultivates compassion and elicits sympathy for those who suffer unfairly, and since it causes us to strive for the good for its own sake, without any promise of reward for good behaviour.[22]

Hick argues that the soul-making process extends beyond our terrestrial existence: “If there is any eventual resolution of the interplay between good and evil, any decisive bringing of good out of evil, it must lie beyond this world and beyond the enigma of death.” Most of us depart from the earth with unfinished lives: “We have not become fully human by the time we die.”[23]

For Hick, belief in the afterlife is “crucial for theodicy,” and his theory leans heavily on the future accomplishment of God’s soul-making design of the world. Sanctification through suffering occurs on the earth and continues after death, “its extent and duration being determined by the degree of unsanctification” we exhibit at death.

In addition, the success of his SMT, and of theodicy in general, depends on the reality of heaven: “Would it not contradict God’s love for the creatures made in His image if He caused them to pass out of existence whilst His purpose for them was still so largely unfulfilled?”[24] Heaven, Hick declares, will “justify retrospectively” and “render worthwhile” all the pain, misery, and injustice of human history and human existence: “And Christian theodicy must point forward to that final blessedness, and claim that this infinite future good will render worthwhile all the pain and travail and wickedness that has occurred on the way to it.”[25] Heaven finally completes the soul-making process and vindicates God.

Thus, with the universalism and the hopefully eschatological vision, SMT seems to be capable of solving the logical or evidential problems of the quantity of natural and moral evil.

Evaluations of The Soul-Making Theodicy

Hick’s theodicy is very appealing in many respects. It seems to explain a maximal amount of evil in our world and does so in a rather plausible way. His theory soundly connects evolutionary science to our spiritual transformation, unfolding its theological and philosophical implications. Moreover, it reinterprets Genesis, the Gospels, and Paul to align scripture with its cosmological and soteriological scheme. Thus, it attempts to bring tradition into conformity with the contemporary world. Furthermore, SMT reconsiders a positive view of suffering as constructive rather than destructive or punitive. Hick’s universalism addresses the problem of dysteleological evil and offer a hopefully eschatological vision of the harmony of all humanity and the eradication of all evil and suffering. Finally, Hick builds his SMT in a positive view of God as a parent who guides humanity through the rigors of spiritual transformation, always with our best interests in mind.

However, that is not to say there have been no objection to SMT. Some of the most substantial objections to Hick’s SMT are found in two articles by G. Stanley Kane. The most significant objection is that moral and spiritual maturity involves developing traits like courage, compassion, and fortitude and that the existence of evils is logically necessary to the development of these traits. Kane disagrees, because “we can imagine situations where these traits could be displayed even though there is no actual evil existing.”[26] Next, Kane criticises Hick’s contention that every soul will eventually be built. If that is so, then what becomes of free will? Isn’t it at least possible that some people will choose forever to reject God? If that is possible, it seems that the only way Hick can guarantee that all will be saved is for God to overrule the freedom of inveterate sinners and force them to comply.[27] This is a serious objection, because it appears that SMT is self-contradictory. Hick recognizes the importance of this objection and notes that it assumes that God can accomplish this goal only if He overrules the wayward wills of human beings. However, this overlooks the point made by Augustine that “in creating our human nature God has formed it for himself, so that our hearts will be restless until they find their rest in him.”[28] In other words, the process of reforming our souls will not be as hard as it seems, because God has created us so that there is an inherent gravitation toward Him. This sounds like determinism after all. To some people, if Hick is serious about maintaining his universalism, he must back down on his notion of freedom. Others, like Feinberg, cannot accept these views because they are contrary to biblical teaching which says a great deal about judgment of the wicked and indicates that many people will not wind up in the kingdom of God.[29]

Nguyễn Duy Vũ

(This is my essay which was originally posted in Nov. 2018 on the Australian Catholic University’s LEO website.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Stump, Eleonore. “The Problem of Evil,” in Philosophy of Religion: The Big Questions, Ed. Eleonore Stump. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Inc., 1999.

Feinberg, John. The Many Faces of Evil. Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994.

Griffin, David. God, power, and evil: a process theodicy. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976.

Hick, John. Evil and the God of Love. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Hick, John. Philosophy of Religion. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 1990.

Hick, John. Death and Eternal Life. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1976.

Hick, John. “Soul-Making Theodicy,” in The Problem of Evil, ed. Michael Peterson. Indiana: Notre Dame Press, 2017.

Hick, John. “An Irenaean Theodicy,” in Encountering Evil: Live Options in Theodicy, ed. Stephen T. Davis. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001.

Kane, Stanley. “The Failure of Soul-Making Theodicy,” in International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 6/1 Spring 1975.

G. Stanley Kane, “Soul-Making

Theodicy and Eschatology,” in Sophia 14,

1975.

[1] John Hick, Evil and the God of Love (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 256.

[2] Ibid., 248.

[3] Ibid., 201.

[4] John Hick, “An Irenaean Theodicy,” in Encountering Evil: Live Options in Theodicy, ed. Stephen T. Davis (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 39.

[5] Hick, Evil and the God of Love, 249.

[6] Ibid., 249.

[7] Hick, Evil and the God of Love, 249.

[8] Ibid., 69.

[9] Ibid., 250.

[10] Ibid., 212.

[11] Hick, “An Irenaean Theodicy,” 40-41.

[12] David Griffin, God, power, and evil: a process theodicy (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976), 176.

[13] Hick, Evil and the God of Love, 176.

[14] Ibid., 253.

[15] Ibid., 254.

[16] Hick, “An Irenaean Theodicy,” 42.

[17] Hick, “An Irenaean Theodicy,” 41.

[18] Hick, Evil and the God of Love, 254.

[19] Ibid., 257.

[20] Hick, Evil and the God of Love, 339.

[21] Ibid., 327, 333-336. Griffin, God, power, and Evil, 189-190.

[22] Hick, Evil and the God of Love, 333-336.

[23] Ibid., 247.

[24] Ibid., 338.

[25] Ibid., 340.

[26] G. Stanley Kane, “The Failure of Soul-Making Theodicy,” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 6/1 (Spring 1975): 2.

[27] G. Stanley Kane, “Soul-Making Theodicy and Eschatology,” Sophia 14 (1975): 27

[28] John Hick, Death and Eternal Life (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1976), 251.

[29] John S. Feinberg, The Many Faces of Evil (Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994), 121.